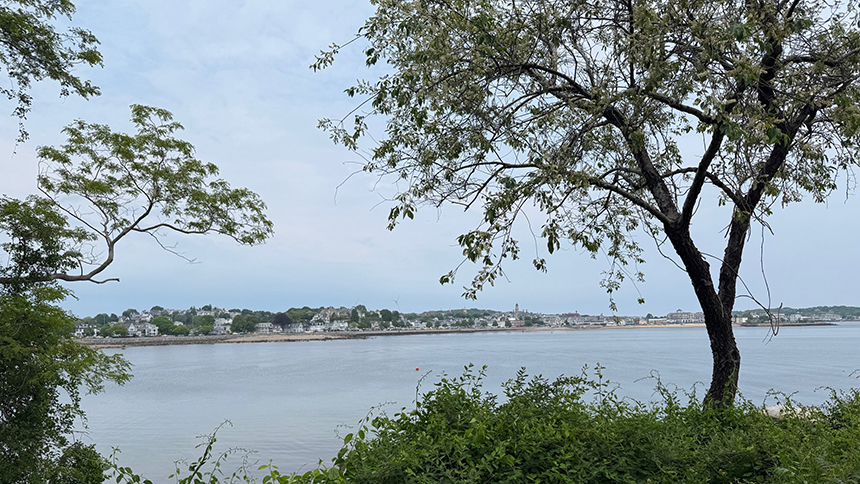

Photo: Faith Palermo

In 1817, a sea serpent appears in Gloucester harbor. On August 14th, creature breaches water, skin kisses air, and is witnessed. The Linnaean Society of New England, a board designed to record and interpret landscape, collects testimony, and the sea serpent becomes the most documented of its kind.

The creature is known in parts: the head of a sea turtle, held a foot above the water – or the head of a rattlesnake, the size of a horse – with a long tongue or prong resembling a fisherman’s harpoon, with oxen eyes and no teeth; a body broken into segments numbering six – or twelve – or fifty, joints bending horizontally to propel motion like a caterpillar; a body with the thickness of a man – or half a barrel – or a two gallon keg; skin unspotted, dark in color – or dark except a nearly white stomach; skin rough and scaled – or smooth, refracting light. The creature is 40 –or 70 – or 120 feet long.

Still, there are points of agreement: the creature moves at a quick clip, travels much faster than whales or (other) fish; the creature bends like a staple, body folding over onto itself; the creature is most frequently seen at dusk; the creature is silent.

On August 14th, shortly after its first sighting, it’s shot. It sinks, not like a fish, but like a rock, like a weight that can’t resist. Yet the creature makes no indication of pain and rises, continues to play, amusing itself amongst the waves. That evening, a boy rows past the creature, could reach out and touch it with calloused hands, but fear keeps anatomy to what is known. The landscape shields the creature – it is too dark for the boy to see, too uncertain for the boy to touch.

Yet, occasionally, the creature lies motionless on the surface of the water, head submerged, floating to the clip of the tide. It’s viewed through spyglasses, close enough to see the texture of skin, but far enough that the creature is unidentifiable. Over the course of a week, the community bands together, creates their own taxonomy. A lithograph is designed, shows a being puzzled together, forked serpentine tongue extended, segments bulging under flesh, but this creature has the teeth of a shark, the huge, hollow eye of a mackerel, is decorated with bands of white flesh. The same schooners that spied the creature sail the image to nearby Boston. The myth of the being precedes them. Despite the deviations, the caption is clear: Sea Serpent.

The Linnaean Society of New England awaits image with open hands, open eyes. They mark discovery, calling for interviews and speculation. In their report, published shortly thereafter, they reference Norway’s gigantic sea snake, claim that this one must be of the same brood, but Gloucester’s creature has to be different, has to be unique. Gloucester’s sea serpent was found in the oldest fishing settlement in the newly freed nation – like the land that surrounds the water, this being too must be claimed as innately American, must tap into something bigger than itself. The Linnaean Society distinguishes it with a new genus: scoliophis atlanticus – or Atlantic Scoliosis, a name derived from shape and location.

As time progresses, the Linnaean Society of New England will claim that they have found a baby scoliophis atlanticus on Gloucester’s shore. They will show it off in their Boston museum until the sample is disproven, identified as a common black snake with physical deformities. Occasionally, the sea creature would be seen peeking up in the harbor or the surrounding open sea, weaving through boats. In 1819, it, or another of its kind, was seen 20 miles away in Nahant. Another sunk a British vessel in 1859. Of course, there’s always speculation: maybe the creature was a pod of narwals, the prong their horn – or maybe a tight pack of whales or seals – or maybe a creature that has since become extinct, a relative of sea faring dinosaurs.

But, for a moment, let’s distance ourselves from truth, look at impact. In August of 1817, the testimony of 13 men, primarily fishermen, was enough to solidify the existence of a sea serpent. Scientists and judges, members of academic communities who comprised the Linnaean Society of New England, played catchup. In the years that follow, Gloucester’s fishermen become romanticized; Longfellow hears of a beached ship manned by survivors and imagines father protecting daughter, tethering her to the mast of a waterlogged ship – in “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” she survives, he drowns. Years later, Diane Lane squints at the horizon from the shore, praying that the green bow of the sunken Andrea Gail will bob into view. The Perfect Storm holds the memory of Gloucester fishermen lost to sea, uses a crew from Florida to epitomize local tragedy. In turn, the mythos of place is assembled around grief and loss, around the exchange of life for livelihood, around those who go down with ships. Yet, in this place of untruth, the sea serpent leaves space for joy: fishermen, accustomed to life on sea, had seen something extraordinary.